This story was first published as part of The Amateur Cracksman in 1899.

It takes place in October, 1891.

Of the various robberies in which we were both concerned, it is but the few, I find, that will bear telling at any length. Not that the others contained details which even I would hesitate to recount; it is, rather, the very absence of untoward incident which renders them useless for my present purpose. In point of fact our plans were so craftily laid (by Raffles) that the chances of a hitch were invariably reduced to a minimum before we went to work. We might be disappointed in the market value of our haul; but it was quite the exception for us to find ourselves confronted by unforeseen impediments, or involved in a really dramatic dilemma. There was a sameness even in our spoil; for, of course, only the most precious stones are worth the trouble we took and the risks we ran. In short, our most successful escapades would prove the greatest weariness of all in narrative form; and none more so than the dull affair of the Ardagh emeralds1, some eight or nine weeks after the Milchester cricket week. The former, however, had a sequel that I would rather forget than all our burglaries put together.

It was the evening after our return from Ireland, and I was waiting at my rooms for Raffles, who had gone off as usual to dispose of the plunder. Raffles had his own method of conducting this very vital branch of our business, which I was well content to leave entirely in his hands. He drove the bargains, I believe, in a thin but subtle disguise of the flashy-seedy order, and always in the Cockney dialect, of which he had made himself a master. Moreover, he invariably employed the same “fence,” who was ostensibly a money-lender in a small (but yet notorious) way, and in reality a rascal as remarkable as Raffles himself. Only lately I also had been to the man, but in my proper person. We had needed capital for the getting of these very emeralds, and I had raised a hundred pounds, on the terms you would expect, from a soft-spoken graybeard with an ingratiating smile, an incessant bow, and the shiftiest old eyes that ever flew from rim to rim of a pair of spectacles. So the original sinews and the final spoils of war2 came in this case from the self-same source—a circumstance which appealed to us both.

But these same final spoils I was still to see, and I waited and waited with an impatience that grew upon me with the growing dusk. At my open window I had played Sister Ann3 until the faces in the street below were no longer distinguishable. And now I was tearing to and fro in the grip of horrible hypotheses—a grip that tightened when at last the lift-gates opened with a clatter outside—that held me breathless until a well-known tattoo followed on my door.

“In the dark!” said Raffles, as I dragged him in. “Why, Bunny, what’s wrong?”

“Nothing—now you’ve come,” said I, shutting the door behind him in a fever of relief and anxiety. “Well? Well? What did they fetch?”

“Five hundred.”

“Down?”

“Got it in my pocket.”

“Good man!” I cried. “You don’t know what a stew I’ve been in. I’ll switch on the light. I’ve been thinking of you and nothing else for the last hour. I—I was ass enough to think something had gone wrong!”

Raffles was smiling when the white light filled the room, but for the moment I did not perceive the peculiarity of his smile. I was fatuously full of my own late tremors and present relief; and my first idiotic act was to spill some whiskey and squirt the soda-water all over in my anxiety to do instant justice to the occasion.

“So you thought something had happened?” said Raffles, leaning back in my chair as he lit a cigarette, and looking much amused. “What would you say if something had? Sit tight, my dear chap! It was nothing of the slightest consequence, and it’s all over now. A stern chase and a long one, Bunny, but I think I’m well to windward this time.”

And suddenly I saw that his collar was limp, his hair matted, his boots thick with dust.

“The police?” I whispered aghast.

“Oh, dear, no; only old Baird 4.”

“Baird! But wasn’t it Baird who took the emeralds?”

“It was.”

“Then how came he to chase you?”

“My dear fellow, I’ll tell you if you give me a chance; it’s really nothing to get in the least excited about. Old Baird has at last spotted that I’m not quite the common cracksman I would have him think me. So he’s been doing his best to run me to my burrow.”

“And you call that nothing!”

“It would be something if he had succeeded; but he has still to do that. I admit, however, that he made me sit up for the time being. It all comes of going on the job so far from home. There was the old brute with the whole thing in his morning paper. He knew it must have been done by some fellow who could pass himself off for a gentleman, and I saw his eyebrows go up the moment I told him I was the man, with the same old twang that you could cut with a paper-knife. I did my best to get out of it—swore I had a pal who was a real swell5—but I saw very plainly that I had given myself away. He gave up haggling. He paid my price as though he enjoyed doing it. But I felt him following me when I made tracks; though, of course, I didn’t turn round to see.”

“Why not?”

“My dear Bunny, it’s the very worst thing you can do. As long as you look unsuspecting they’ll keep their distance, and so long as they keep their distance you stand a chance. Once show that you know you’re being followed, and it’s flight or fight for all you’re worth. I never even looked round; and mind you never do in the same hole. I just hurried up to Blackfriars and booked for High Street, Kensington, at the top of my voice; and as the train was leaving Sloane Square out I hopped, and up all those stairs like a lamplighter6, and round to the studio by the back streets. Well, to be on the safe side, I lay low there all the afternoon, hearing nothing in the least suspicious, and only wishing I had a window to look through instead of that beastly skylight. However, the coast seemed clear enough, and thus far it was my mere idea that he would follow me; there was nothing to show he had. So at last I marched out in my proper rig—almost straight into old Baird’s arms!”

“What on earth did you do?”

“Walked past him as though I had never set eyes on him in my life, and didn’t then; took a hansom in the King’s Road, and drove like the deuce to Clapham Junction; rushed on to the nearest platform, without a ticket7, jumped into the first train I saw, got out at Twickenham, walked full tilt back to Richmond, took the District8 to Charing Cross, and here I am! Ready for a tub and a change, and the best dinner the club can give us. I came to you first, because I thought you might be getting anxious. Come round with me, and I won’t keep you long.”

“You’re certain you’ve given him the slip?” I said, as we put on our hats.

“Certain enough; but we can make assurance doubly sure9,” said Raffles, and went to my window, where he stood for a moment or two looking down into the street.

“All right?” I asked him.

“All right,” said he; and we went downstairs forthwith, and so to the Albany arm-in-arm.10

But we were both rather silent on our way. I, for my part, was wondering what Raffles would do about the studio in Chelsea, whither, at all events, he had been successfully dogged. To me the point seemed one of immediate importance, but when I mentioned it he said there was time enough to think about that. His one other remark was made after we had nodded (in Bond Street) to a young blood of our acquaintance who happened to be getting himself a bad name.

“Poor Jack Rutter!” said Raffles, with a sigh. “Nothing’s sadder than to see a fellow going to the bad like that. He’s about mad with drink and debt, poor devil! Did you see his eye? Odd that we should have met him to-night, by the way; it’s old Baird who’s said to have skinned him. By God, but I’d like to skin old Baird!”

And his tone took a sudden low fury, made the more noticeable by another long silence, which lasted, indeed, throughout an admirable dinner at the club, and for some time after we had settled down in a quiet corner of the smoking-room with our coffee and cigars. Then at last I saw Raffles looking at me with his lazy smile, and I knew that the morose fit was at an end.

“I daresay you wonder what I’ve been thinking about all this time?” said he. “I’ve been thinking what rot it is to go doing things by halves!”

“Well,” said I, returning his smile, “that’s not a charge that you can bring against yourself, is it?”

“I’m not so sure,” said Raffles, blowing a meditative puff; “as a matter of fact, I was thinking less of myself than of that poor devil of a Jack Rutter. There’s a fellow who does things by halves; he’s only half gone to the bad; and look at the difference between him and us! He’s under the thumb of a villainous money-lender; we are solvent citizens. He’s taken to drink; we’re as sober as we are solvent. His pals are beginning to cut him11; our difficulty is to keep the pal from the door. Enfin12, he begs or borrows, which is stealing by halves; and we steal outright and are done with it. Obviously ours is the more honest course. Yet I’m not sure, Bunny, but we’re doing the thing by halves ourselves!”

“Why? What more could we do?” I exclaimed in soft derision, looking round, however, to make sure that we were not overheard.

“What more,” said Raffles. “Well, murder—for one thing.”

“Rot!”

“A matter of opinion, my dear Bunny; I don’t mean it for rot. I’ve told you before that the biggest man alive is the man who’s committed a murder, and not yet been found out; at least he ought to be, but he so very seldom has the soul to appreciate himself. Just think of it! Think of coming in here and talking to the men, very likely about the murder itself; and knowing you’ve done it; and wondering how they’d look if they knew! Oh, it would be great, simply great! But, besides all that, when you were caught there’d be a merciful and dramatic end of you. You’d fill the bill for a few weeks, and then snuff out with a flourish of extra-specials13; you wouldn’t rust with a vile repose14 for seven or fourteen years.15”

“Good old Raffles!” I chuckled. “I begin to forgive you for being in bad form at dinner.”

“But I was never more earnest in my life.”

“Go on!”

“I mean it.”

“You know very well that you wouldn’t commit a murder, whatever else you might do.”

“I know very well I’m going to commit one to-night!”

He had been leaning back in the saddle-bag chair16, watching me with keen eyes sheathed by languid lids; now he started forward, and his eyes leapt to mine like cold steel from the scabbard. They struck home to my slow wits; their meaning was no longer in doubt. I, who knew the man, read murder in his clenched hands, and murder in his locked lips, but a hundred murders in those hard blue eyes.

“Baird?” I faltered, moistening my lips with my tongue.

“Of course.”

“But you said it didn’t matter about the room in Chelsea?”

“I told a lie.”

“Anyway you gave him the slip afterwards!”

“That was another. I didn’t. I thought I had when I came up to you this evening; but when I looked out of your window—you remember? to make assurance doubly sure—there he was on the opposite pavement down below.”

“And you never said a word about it!”

“I wasn’t going to spoil your dinner, Bunny, and I wasn’t going to let you spoil mine. But there he was as large as life, and, of course, he followed us to the Albany. A fine game for him to play, a game after his mean17 old heart: blackmail from me, bribes from the police, the one bidding against the other; but he sha’n’t play it with me, he sha’n’t live to, and the world will have an extortioner the less. Waiter! Two Scotch whiskeys and sodas. I’m off at eleven, Bunny; it’s the only thing to be done.”

“You know where he lives, then?”

“Yes, out Willesden18 way, and alone; the fellow’s a miser among other things. I long ago found out all about him.”

Again I looked round the room; it was a young man’s club, and young men were laughing, chatting, smoking, drinking, on every hand. One nodded to me through the smoke. Like a machine I nodded to him, and turned back to Raffles with a groan.

“Surely you will give him a chance!” I urged. “The very sight of your pistol should bring him to terms.”

“It wouldn’t make him keep them.”

“But you might try the effect?”

“I probably shall. Here’s a drink for you, Bunny. Wish me luck.”

“I’m coming too.”

“I don’t want you.”

“But I must come!”

An ugly gleam shot from the steel blue eyes19.

“To interfere?” said Raffles.

“Not I.”

“You give me your word?”

“I do.”

“Bunny, if you break it—”

“You may shoot me, too!”

“I most certainly should,” said Raffles, solemnly. “So you come at your own peril, my dear man; but, if you are coming—well, the sooner the better, for I must stop at my rooms on the way.”

Five minutes later I was waiting for him at the Piccadilly entrance to the Albany. I had a reason for remaining outside. It was the feeling—half hope, half fear—that Angus Baird might still be on our trail—that some more immediate and less cold-blooded way of dealing with him might result from a sudden encounter between the money-lender and myself. I would not warn him of his danger; but I would avert tragedy at all costs. And when no such encounter had taken place, and Raffles and I were fairly on our way to Willesden, that, I think, was still my honest resolve. I would not break my word if I could help it, but it was a comfort to feel that I could break it if I liked, on an understood penalty. Alas! I fear my good intentions were tainted with a devouring curiosity, and overlaid by the fascination which goes hand in hand with horror.

I have a poignant recollection of the hour it took us to reach the house. We walked across St. James’s Park (I can see the lights now, bright on the bridge and blurred in the water), and we had some minutes to wait for the last train to Willesden. It left at 11.21, I remember, and Raffles was put out to find it did not go on to Kensal Rise20. We had to get out at Willesden Junction and walk on through the streets into fairly open country that happened to be quite new to me. I could never find the house again. I remember, however, that we were on a dark footpath between woods and fields when the clocks began striking twelve.

“Surely,” said I, “we shall find him in bed and asleep?”

“I hope we do,” said Raffles grimly.

“Then you mean to break in?”

“What else did you think?”

I had not thought about it at all; the ultimate crime had monopolized my mind. Beside it burglary was a bagatelle, but one to deprecate none the less. I saw obvious objections: the man was au fait21 with cracksmen and their ways: he would certainly have firearms, and might be the first to use them.

“I could wish nothing better,” said Raffles. “Then it will be man to man, and devil take the worst shot. You don’t suppose I prefer foul play to fair, do you? But die he must, by one or the other, or it’s a long stretch for you and me.”

“Better that than this!”

“Then stay where you are, my good fellow. I told you I didn’t want you; and this is the house. So good-night.”

I could see no house at all, only the angle of a high wall rising solitary in the night, with the starlight glittering on battlements of broken glass22; and in the wall a tall green gate, bristling with spikes, and showing a front for battering-rams in the feeble rays an outlying lamp-post cast across the new-made road. It seemed to me a road of building-sites, with but this one house built, all by itself, at one end; but the night was too dark for more than a mere impression.

Raffles, however, had seen the place by daylight, and had come prepared for the special obstacles; already he was reaching up and putting champagne corks on the spikes, and in another moment he had his folded covert-coat across the corks. I stepped back as he raised himself, and saw a little pyramid of slates snip the sky above the gate; as he squirmed over I ran forward, and had my own weight on the spikes and corks and covert-coat when he gave the latter a tug.

“Coming after all?”

“Rather!”

“Take care, then; the place is all bell-wires and springs23. It’s no soft thing, this! There—stand still while I take off the corks.”

The garden was very small and new, with a grass-plot still in separate sods, but a quantity of full-grown laurels stuck into the raw clay beds. “Bells in themselves,” as Raffles whispered; “there’s nothing else rustles so—cunning old beast!” And we gave them a wide berth as we crept across the grass.

“He’s gone to bed!”

“I don’t think so, Bunny. I believe he’s seen us.”

“Why?”

“I saw a light.”

“Where?”

“Downstairs, for an instant, when I—”

His whisper died away; he had seen the light again; and so had I.

It lay like a golden rod under the front-door—and vanished. It reappeared like a gold thread under the lintel—and vanished for good. We heard the stairs creak, creak, and cease, also for good. We neither saw nor heard any more, though we stood waiting on the grass till our feet were soaked with the dew.

“I’m going in,” said Raffles at last. “I don’t believe he saw us at all. I wish he had. This way.”

We trod gingerly on the path, but the gravel stuck to our wet soles, and grated horribly in a little tiled veranda with a glass door leading within. It was through this glass that Raffles had first seen the light; and he now proceeded to take out a pane, with the diamond, the pot of treacle24, and the sheet of brown paper which were seldom omitted from his impedimenta. Nor did he dispense with my own assistance, though he may have accepted it as instinctively as it was proffered. In any case it was these fingers that helped to spread the treacle on the brown paper, and pressed the latter to the glass until the diamond had completed its circuit and the pane fell gently back into our hands.

Raffles now inserted his hand, turned the key in the lock, and, by making a long arm, succeeded in drawing the bolt at the bottom of the door; it proved to be the only one, and the door opened, though not very wide.

“What’s that?” said Raffles, as something crunched beneath his feet on the very threshold.

“A pair of spectacles,” I whispered, picking them up. I was still fingering the broken lenses and the bent rims when Raffles tripped and almost fell, with a gasping cry that he made no effort to restrain.

“Hush, man, hush!” I entreated under my breath. “He’ll hear you!”

For answer his teeth chattered—even his—and I heard him fumbling with his matches. “No, Bunny; he won’t hear us,” whispered Raffles, presently; and he rose from his knees and lit a gas as the match burnt down.

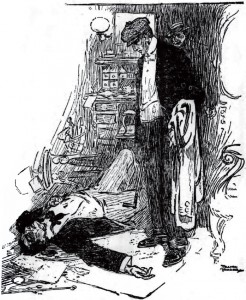

Angus Baird was lying on his own floor, dead, with his gray hairs glued together by his blood; near him a poker with the black end glistening; in a corner his desk, ransacked, littered. A clock ticked noisily on the chimney-piece; for perhaps a hundred seconds there was no other sound.25

Raffles stood very still, staring down at the dead, as a man might stare into an abyss after striding blindly to its brink. His breath came audibly through wide nostrils; he made no other sign, and his lips seemed sealed.

“That light!” said I, hoarsely; “the light we saw under the door!”

With a start he turned to me.

“It’s true! I had forgotten it. It was in here I saw it first!”

“He must be upstairs still!”

“If he is we’ll soon rout him out. Come on!”

Instead I laid a hand upon his arm, imploring him to reflect—that his enemy was dead now—that we should certainly be involved—that now or never was our own time to escape. He shook me off in a sudden fury of impatience, a reckless contempt in his eyes, and, bidding me save my own skin if I liked, he once more turned his back upon me, and this time left me half resolved to take him at his word. Had he forgotten on what errand he himself was here? Was he determined that this night should end in black disaster? As I asked myself these questions his match flared in the hall; in another moment the stairs were creaking under his feet, even as they had creaked under those of the murderer; and the humane instinct that inspired him in defiance of his risk was borne in also upon my slower sensibilities. Could we let the murderer go? My answer was to bound up the creaking stairs and to overhaul26 Raffles on the landing.

But three doors presented themselves; the first opened into a bedroom with the bed turned down but undisturbed; the second room was empty in every sense; the third door was locked.

Raffles lit the landing gas.

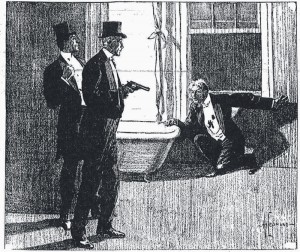

“He’s in there,” said he, cocking his revolver. “Do you remember how we used to break into the studies at school? Here goes!”

His flat foot crashed over the keyhole, the lock gave, the door flew open, and in the sudden draught the landing gas heeled over like a cobble27 in a squall; as the flame righted itself I saw a fixed bath, two bath-towels knotted together—an open window—a cowering figure—and Raffles struck aghast on the threshold.

“Jack—Rutter?”28

The words came thick and slow with horror, and in horror I heard myself repeating them, while the cowering figure by the bathroom window rose gradually erect.

“It’s you!” he whispered, in amazement no less than our own; “it’s you two! What’s it mean, Raffles? I saw you get over the gate; a bell rang, the place is full of them. Then you broke in. What’s it all mean?”

“We may tell you that, when you tell us what in God’s name you’ve done, Rutter!”

“Done? What have I done?” The unhappy wretch came out into the light with bloodshot, blinking eyes, and a bloody shirt-front. “You know—you’ve seen—but I’ll tell you if you like. I’ve killed a robber; that’s all. I’ve killed a robber, a usurer, a jackal, a blackmailer, the cleverest and the cruellest villain unhung. I’m ready to hang for him. I’d kill him again!”

And he looked us fiercely in the face, a fine defiance in his dissipated eyes; his breast heaving, his jaw like a rock.

“Shall I tell you how it happened?” he went passionately on. “He’s made my life a hell these weeks and months past. You may know that. A perfect hell! Well, to-night I met him in Bond Street. Do you remember when I met you fellows? He wasn’t twenty yards behind you; he was on your tracks, Raffles; he saw me nod to you, and stopped me and asked me who you were. He seemed as keen as knives to know, I couldn’t think why, and didn’t care either, for I saw my chance. I said I’d tell him all about you if he’d give me a private interview. He said he wouldn’t. I said he should, and held him by the coat; by the time I let him go you were out of sight, and I waited where I was till he came back in despair. I had the whip-hand of him then. I could dictate where the interview should be, and I made him take me home with him, still swearing to tell him all about you when we’d had our talk. Well, when we got here I made him give me something to eat, putting him off and off; and about ten o’clock I heard the gate shut. I waited a bit, and then asked him if he lived alone.

“‘Not at all,’ says he; ‘did you not see the servant?’

“I said I’d seen her, but I thought I’d heard her go; if I was mistaken no doubt she would come when she was called; and I yelled three times at the top of my voice. Of course there was no servant to come. I knew that, because I came to see him one night last week, and he interviewed me himself through the gate, but wouldn’t open it. Well, when I had done yelling, and not a soul had come near us, he was as white as that ceiling. Then I told him we could have our chat at last; and I picked the poker out of the fender, and told him how he’d robbed me, but, by God, he shouldn’t rob me any more. I gave him three minutes to write and sign a settlement of all his iniquitous claims against me, or have his brains beaten out over his own carpet. He thought a minute, and then went to his desk for pen and paper. In two seconds he was round like lightning with a revolver, and I went for him bald-headed. He fired two or three times and missed; you can find the holes if you like; but I hit him every time—my God! I was like a savage till the thing was done. And then I didn’t care. I went through his desk looking for my own bills, and was coming away when you turned up. I said I didn’t care, nor do I; but I was going to give myself up to-night, and shall still; so you see I sha’n’t give you fellows much trouble!”

He was done; and there we stood on the landing of the lonely house, the low, thick, eager voice still racing and ringing through our ears; the dead man below, and in front of us his impenitent slayer. I knew to whom the impenitence would appeal when he had heard the story, and I was not mistaken.

“That’s all rot,” said Raffles, speaking after a pause; “we sha’n’t let you give yourself up.”

“You sha’n’t stop me! What would be the good? The woman saw me; it would only be a question of time; and I can’t face waiting to be taken. Think of it: waiting for them to touch you on the shoulder! No, no, no; I’ll give myself up and get it over.”

His speech was changed; he faltered, floundered. It was as though a clearer perception of his position had come with the bare idea of escape from it.

“But listen to me,” urged Raffles; “We’re here at our peril ourselves. We broke in like thieves to enforce redress for a grievance very like your own. But don’t you see? We took out a pane—did the thing like regular burglars. Regular burglars will get the credit of all the rest!”

“You mean that I sha’n’t be suspected?”

“I do.”

“But I don’t want to get off scotfree,” cried Rutter hysterically. “I’ve killed him. I know that. But it was in self-defence; it wasn’t murder29 I must own up and take the consequences. I shall go mad if I don’t!”

His hands twitched; his lips quivered; the tears were in his eyes. Raffles took him roughly by the shoulder.

“Look here, you fool! If the three of us were caught here now, do you know what those consequences would be? We should swing in a row at Newgate in six weeks’ time! You talk as though we were sitting in a club; don’t you know it’s one o’clock in the morning, and the lights on, and a dead man down below? For God’s sake pull yourself together, and do what I tell you, or you’re a dead man yourself.”

“I wish I was one!” Rutter sobbed. “I wish I had his revolver to blow my own brains out. It’s lying under him. O my God, my God!”

His knees knocked together: the frenzy of reaction was at its height. We had to take him downstairs between us, and so through the front door out into the open air.

All was still outside—all but the smothered weeping of the unstrung wretch upon our hands. Raffles returned for a moment to the house; then all was dark as well. The gate opened from within; we closed it carefully behind us; and so left the starlight shining on broken glass and polished spikes, one and all as we had found them.

We escaped; no need to dwell on our escape. Our murderer seemed set upon the scaffold—drunk with his deed, he was more trouble than six men drunk with wine. Again and again we threatened to leave him to his fate, to wash our hands of him. But incredible and unmerited luck was with the three of us. Not a soul did we meet between that and Willesden; and of those who saw us later, did one think of the two young men with crooked white ties, supporting a third in a seemingly unmistakable condition, when the evening papers apprised the town of a terrible tragedy at Kensal Rise?

We walked to Maida Vale, and thence drove openly to my rooms. But I alone went upstairs; the other two proceeded to the Albany, and I saw no more of Raffles for forty-eight hours. He was not at his rooms when I called in the morning; he had left no word. When he reappeared the papers were full of the murder; and the man who had committed it was on the wide Atlantic, a steerage passenger from Liverpool to New York.

“There was no arguing with him,” so Raffles told me; “either he must make a clean breast of it or flee the country. So I rigged him up at the studio, and we took the first train to Liverpool. Nothing would induce him to sit tight and enjoy the situation as I should have endeavored to do in his place; and it’s just as well! I went to his diggings to destroy some papers, and what do you think I found. The police in possession; there’s a warrant out against him already! The idiots think that window wasn’t genuine, and the warrant’s out. It won’t be my fault if it’s ever served!”

Nor, after all these years, can I think it will be mine.