Mr. Levy sailed in with frock-coat flying, shiny hat in hand; he was evidently prepared for us, and Raffles for once behaved as though we were prepared for Mr. Levy. Of myself I cannot speak. I was ready for a terrific scene. But Raffles was magnificent, and to do our enemy justice he was quite as good; they faced each other with a nod and a smile of mutual suavity, shot with underlying animosity on the one side and delightful defiance on the other. Not a word was said or a tone employed to betray the true situation between the three of us; for I took my cue from the two protagonists just in time to preserve the triple truce. Meanwhile Mr. Garland, obviously distressed as he was, and really ill as he looked, was not the least successful of us in hiding his emotions; for having expressed a grim satisfaction in the coincidence of our all knowing each other, he added that he supposed Miss Belsize was an exception, and presented Mr. Levy forthwith as though he were an ordinary guest.

“You must find a better exception than this young lady!” cried that worthy with a certain aplomb. “I know you very well by sight, Miss Belsize, and your mother, Lady Laura, into the bargain.”

“Really?” said Miss Belsize, without returning the compliment at her command.

“The bargain!” muttered Raffles to me with sly irony. The echo was not meant for Levy’s ears, but it reached them nevertheless, and was taken up with adroit urbanity.

“I didn’t mean to use a trade term,” explained the Jew, “though bargains, I confess, are somewhat in my line; and I don’t often get the worst of one, Mr. Raffles; when I do, the other fellow usually lives to repent it.”

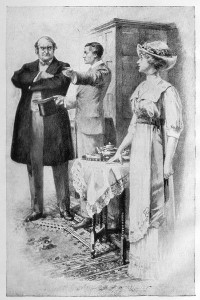

It was said with a laugh for the lady’s benefit, but with a gleam of the eyes for ours. Raffles answered the laugh with a much heartier one; the look he ignored. I saw Miss Belsize beginning to watch the pair, and only interrupted by the arrival of the tea-tray, over which Mr. Garland begged her to preside. Mr. Garland seemed to have an anxious eye upon us all in turn; at Raffles he looked wistfully as though burning to get him to himself for further consultation; but the fact that he refrained from doing so, coupled with a grimly punctilious manner towards the money-lender, gave the impression that his son’s whereabouts was no longer the sole anxiety.

“And yet,” remarked Miss Belsize, as we formed a group about her in the firelight, “you seem to have met your match the other day, Mr. Levy?”

“Where was that, Miss Belsize?”

“Somewhere on the Continent, wasn’t it? It got into the newspapers, I know, but I forget the name of the place.”

“Do you mean when my wife and I were robbed at Carlsbad?”

I was holding my breath now as I had not held it all day. Raffles was merely smiling into his teacup as one who knew all about the affair.

“Carlsbad it was!” certified Miss Belsize, as though it mattered. “I remember now.”

“I don’t call that meeting your match,” said the money-lender. “An unarmed man with a frightened wife at his elbow is no match for a desperate criminal with a loaded revolver.”

“Was it as bad as all that?” whispered Camilla Belsize.

Up to this point one had felt her to be forcing the unlucky topic with the best of intentions towards us all; now she was interested in the episode for its own sake, and eager for more details than Mr. Levy had a mind to impart.

“It makes a good tale, I know,” said he, “but I shall prefer telling it when they’ve got the man. If you want to know any more, Miss Belsize, you’d better ask Mr. Raffles; ‘e was in our hotel, and came in for all the excitement. But it was just a trifle too exciting for me and my wife.”

“Raffles at Carlsbad?” exclaimed Mr. Garland.

Miss Belsize only stared.

“Yes,” said Raffles. “That’s where I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Levy.”

“Didn’t you know he was there?” inquired the money-lender of our host. And he looked sharply at Raffles as Mr. Garland replied that this was the first he had heard of it.

“But it’s the first we’ve seen of each other, sir,” said Raffles, “except those few minutes this morning. And I told you I only got back last night.”

“But you never told me you had been at Carlsbad, Raffles!”

“It’s a sore subject, you see,” said Raffles, with a sigh and a laugh. “Isn’t it, Mr. Levy?”

“You seem to find it so,” replied the moneylender.

They were standing face to face in the firelight, each with a shoulder against the massive chimney-piece; and Camilla Belsize was still staring at them both from her place behind the tea-tray; and I was watching the three of them by turns from the other side of the hall.

“But you’re the fittest man I know. Raffles,” pursued old Garland with terrible tact. “What on earth were you doing at a place like Carlsbad?”

“The cure,” said Raffles. “There’s nothing else to do there—is there, Mr. Levy?”

Levy replied with his eyes on Raffles:

“Unless you’ve got to cope with a swell mobsman who steals your wife’s jewels and then gets in such a funk that he practically gives them back again!”

The emphasised term was the one that Dan Levy had applied to Raffles and myself in his own office that very morning.

“Did he give them back again?” asked Camilla Belsize, breaking her silence on an eager note.

Raffles turned to her at once.

“The jewels were found buried in the woods,” said he. “Out there everybody thought the thief had simply hidden them. But no doubt Mr. Levy has the better information.”

Mr. Levy smiled sardonically in the firelight. And it was at this point I followed the example of Miss Belsize and put in my one belated word.

“I shouldn’t have thought there was such a thing as a swell mob in the wilds of Austria,” said I.

“There isn’t,” admitted the money-lender readily. “But your true mobsman knows his whole blooming Continent as well as Piccadilly Circus. His ‘ead-quarters are in London, but a week’s journey at an hour’s notice is nothing to him if the swag looks worth it. Mrs. Levy’s necklace was actually taken at Carlsbad, for instance, but the odds are that it was marked down at some London theatre—or restaurant, eh, Mr. Raffles?”

“I’m afraid I can’t offer an expert opinion,” said Raffles very merrily as their eyes met. “But if the man was an Englishman and knew that you were one, why didn’t he bully you in the vulgar tongue?”

“Who told you he didn’t?” cried Levy, with a sudden grin that left no doubt about the thought behind it. To me that thought had been obvious from its birth within the last few minutes; but this expression of it was as obvious a mistake.

“Who told me anything about it,” retorted Raffles, “except yourself and Mrs. Levy? Your gospels clashed a little here and there; but both agreed that the fellow threatened you in German as well as with a revolver.”

“We thought it was German,” rejoined Levy, with dexterity. “It might ‘ave been ‘Industani or ‘Eathen Chinee for all I know! But there was no error about the revolver. I can see it covering me, and his shooting eye looking along the barrel into mine—as plainly as I’m looking into yours now, Mr. Raffles.”

Raffles laughed outright.

“I hope I’m a pleasanter spectacle, Mr. Levy? I remember your telling me that the other fellow looked the most colossal cut-throat.”

“So he did,” said Levy; “he looked a good deal worse than he need to have done. His face was blackened and disguised, but his teeth were as white as yours are.”

“Any other little point in common?”

“I had a good look at the hand that pointed the revolver.”

Raffles held out his hands.

“Better have a good look at mine.”

“His were as black as his face, but even yours are no smoother or better kept.”

“Well, I hope you’ll clap the bracelets on them yet, Mr. Levy.”

“You’ll get your wish, I promise you, Mr. Raffles.”

“You don’t mean to say you’ve spotted your man?” cried A.J. airily.

“I’ve got my eye on him!” replied Dan Levy, looking Raffles through and through.

“And won’t you tell us who he is?” asked Raffles, returning that deadly look with smiling interest, but answering a tone as deadly in one that maintained the note of persiflage in spite of Daniel Levy.

For Levy alone had changed the key with his last words; to that point I declare the whole passage might have gone for banter before the keenest eyes and the sharpest ears in Europe. I alone could know what a duel the two men were fighting behind their smiles. I alone could follow the finer shades, the mutual play of glance and gesture, the subtle tide of covert battle. So now I saw Levy debating with himself as to whether he should accept this impudent challenge and denounce Raffles there and then. I saw him hesitate, saw him reflect. The crafty, coarse, emphatic face was easily read; and when it suddenly lit up with a baleful light, I felt we might be on our guard against something more malign than mere reckless denunciation.

“Yes!” whispered a voice I hardly recognised. “Won’t you tell us who it was?”

“Not yet,” replied Levy, still looking Raffles full in the eyes. “But I know all about him now!”

I looked at Miss Belsize; she it was who had spoken, her pale face set, her pale lips trembling. I remembered her many questions about Raffles during the morning. And I began to wonder whether after all I was the only entirely understanding witness of what had passed here in the firelit hall.

Mr. Garland, at any rate, had no inkling of the truth. Yet even in that kindly face there was a vague indignation and distress, though it passed almost as our eyes met. Into his there had come a sudden light; he sprang up as one alike rejuvenated and transfigured; there was a quick step in the porch, and next instant the truant Teddy was in our midst.

Mr. Garland met him with outstretched hand but not a question or a syllable of surprise; it was Teddy who uttered the cry of joy, who stood gazing at his father and raining questions upon him as though they had the hall to themselves. What was all this in the evening papers? Who had put it in? Was there any truth in it at all?

“None, Teddy,” said Mr. Garland, with some bitterness; “my health was never better in my life.”

“Then I can’t understand it,” cried the son, with savage simplicity. “I suppose it’s some rotten practical joke; if so, I would give something to lay hands on the joker!”

His father was still the only one of us he seemed to see, or could bring himself to face in his distress. Not that young Garland had the appearance of one who had been through fresh vicissitudes; on the contrary, he looked both trimmer and ruddier than overnight; and in his sudden fit of passionate indignation, twice the man that one remembered so humiliated and abased.

Raffles came forward from the fireside.

“There are some of us,” said he, “who won’t be so hard on the beggar for bringing you back from Lord’s at last! You must remember that I’m the only one here who has been up there at all, or seen anything of you all day.”

Their eyes met; and for one moment I thought that Teddy Garland was going to repudiate this cool suggestio falsi1, and tell us all where he had really been; but that was now impossible without giving Raffles away, and then there was his Camilla in evident ignorance of the disappearance which he had expected to find common property. The double circumstance was too strong for him; he took her hand with a confused apology which was not even necessary. Anybody could see that the boy had burst among us with eyes for his father only, and thoughts of nothing but the report about his health; as for Miss Belsize, she looked as though she liked him the better for it, or it may have been for an excitability rare in him and rarely becoming. His pink face burnt like a flame. His eyes were brilliant; they met mine at last, and I was warmly greeted; but their friendly light burst into a blaze of wrath as almost simultaneously they fell upon his bugbear in the background.

“So you’ve kept your threat, Mr. Levy!” said young Garland, quietly enough once he had found his voice.

“I generally do,” remarked the money-lender, with a malevolent laugh.

“His threat!” cried Mr. Garland sharply. “What are you talking about, Teddy?”

“I will tell you,” said the young man. “And you, too!” he added almost harshly, as Camilla Belsize rose as though about to withdraw. “You may as well know what I am—while there’s time. I got into debt—I borrowed from this man.”

“You borrowed from him?”

It was Mr. Garland speaking in a voice hard to recognise, with an emphasis harder still to understand; and as he spoke he glared at Levy with new loathing and abhorrence.

“Yes,” said Teddy; “he had been pestering me with his beastly circulars every week of my first year at Cambridge. He even wrote to me in his own fist. It was as though he knew something about me and meant getting me in his clutches; and he got me all right in the end, and bled me to the last drop as I deserved. I don’t complain so far as I’m concerned. It serves me right. But I did mean to get through without coming to you again, father! I was fool enough to tell him so the other day; that was when he threatened to come to you himself. But I didn’t think he was such a brute as to come to-day!”

“Or such a fool?” suggested Raffles, as he put a piece of paper into Teddy’s hands.

It was his own original promissory note, the one we had recovered from Dan Levy in the morning. Teddy glanced at it, clutched Raffles by the hand, and went up to the money-lender as though he meant to take him by the throat before us all.

“Does this mean that we’re square?” he asked hoarsely.

“It means that you are,” replied Dan Levy.

“In fact it amounts to your receipt for every penny I ever owed you?”

“Every penny that you owed me, certainly.”

“Yet you must come to my father all the same; you must have it both ways—your money and your spite as well!”

“Put it that way if you like,” said Levy, with a shrug of his massive shoulders. “It isn’t the case, but what does that matter so long as you’re ‘appy?”

“No,” said Teddy through his teeth; “nothing matters now that I’ve come back in time.”

“In time for what?”

“To turn you out of the house if you don’t clear out this instant!”

The great gross man looked upon his athletic young opponent, and folded his arms with a guttural chuckle.

“So you mean to chuck me out, do you?”

“By all my gods2, if you make me, Mr. Levy! Here’s your hat; there’s the door; and never you dare to set foot in this house again.”

The money-lender took his shiny topper, gave it a meditative polish with his sleeve, and actually went as bidden to the threshold of the porch; but I saw the suppression of a grin beneath the pendulous nose, a cunning twinkle in the inscrutable eyes, and it did not astonish me when the fellow turned to deliver a Parthian shot3. I was only surprised at the harmless character of the shot.

“May I ask whose house it is?” were his words, in themselves notable chiefly for the aspirates of undue deliberation.

“Not mine, I know; but I’m the son of the house,” returned Teddy truculently, “and out you go!”

“Are you so sure that it’s even your father’s house?” inquired Levy with the deadly suavity of which he was capable when he liked. A groan from Mr. Garland confirmed the doubt implied in the words.

“The whole place is his,” declared the son, with a sort of nervous scorn— “freehold4 and everything.”

“The whole place happens to be mine—’freehold and everything!'” replied Levy, spitting his iced poison in separate syllables. “And as for clearing out, that’ll be your job, and I’ve given you a week to do it in—the two of you!”

He stood a moment in the open doorway, towering in his triumph, glaring on us all in turn, but at Raffles longest and last of all.

“And you needn’t think you’re going to save the old man,” came with a passionate hiss, “like you did the son—because I know all about you now!”