This story was first published in Scribner’s Magazine in the May 1901 issue.

I

Society persons are not likely to have forgotten the series of audacious robberies by which so many of themselves suffered in turn during the brief course of a recent season. Raid after raid was made upon the smartest houses in town, and within a few weeks more than one exalted head had been shorn of its priceless tiara. The Duke and Duchess of Dorchester lost half the portable pieces of their historic plate1 on the very night of their Graces’ almost equally historic costume ball. The Kenworthy diamonds were taken in broad daylight, during the excitement of a charitable meeting on the ground floor, and the gifts of her belted bridegroom2 to Lady May Paulton while the outer air was thick with a prismatic shower of confetti. It was obvious that all this was the work of no ordinary thief, and perhaps inevitable that the name of Raffles should have been dragged from oblivion by callous disrespecters of the departed and unreasoning apologists for the police. These wiseacres did not hesitate to bring a dead man back to life because they knew of no living one capable of such feats; it is their heedless and inconsequent calumnies that the present paper is partly intended to refute. As a matter of fact, our joint innocence in this matter was only exceeded by our common envy, and for a long time, like the rest of the world, neither of us had the slightest clew to the identity of the person who was following in our steps with such irritating results.

“I should mind less,” said Raffles, “if the fellow were really playing my game. But abuse of hospitality was never one of my strokes3, and it seems to me the only shot he’s got. When we took old Lady Melrose’s necklace, Bunny, we were not staying with the Melroses, if you recollect.”

We were discussing the robberies for the hundredth time, but for once under conditions more favorable to animated conversation than our unique circumstances permitted in the flat. We did not often dine out. Dr. Theobald was one impediment, the risk of recognition was another. But there were exceptions, when the doctor was away or the patient defiant, and on these rare occasions we frequented a certain unpretentious restaurant in the Fulham quarter4, where the cooking was plain but excellent, and the cellar a surprise. Our bottle of ’89 champagne was empty to the label when the subject arose, to be touched by Raffles in the reminiscent manner indicated above. I can see his clear eye upon me now, reading me, weighing me. But I was not so sensitive to his scrutiny at the time. His tone was deliberate, calculating, preparatory; not as I heard it then, through a head full of wine, but as it floats back to me across the gulf between that moment and this.

“Excellent fillet!” said I, grossly. “So you think this chap is as much in society as we were, do you?”

I preferred not to think so myself. We had cause enough for jealousy without that. But Raffles raised his eyebrows an eloquent half-inch.

“As much, my dear Bunny? He is not only in it, but of it; there’s no comparison between us there. Society is in rings like a target, and we never were in the bull’s-eye, however thick you may lay on the ink! I was asked for my cricket. I haven’t forgotten it yet5. But this fellow’s one of themselves, with the right of entrée into the houses which we could only ‘enter’ in a professional sense. That’s obvious unless all these little exploits are the work of different hands, which they as obviously are not. And it’s why I’d give five hundred pounds to put salt on him to-night!”

“Not you,” said I, as I drained my glass in festive incredulity.

“But I would, my dear Bunny. Waiter! another half-bottle of this,” and Raffles leant across the table as the empty one was taken away. “I never was more serious in my life,” he continued below his breath. “Whatever else our successor may be, he’s not a dead man like me, or a marked man like you. If there’s any truth in my theory he’s one of the last people upon whom suspicion is ever likely to rest; and oh, Bunny, what a partner he would make for you and me!”

Under less genial influences the very idea of a third partner would have filled my soul with offence; but Raffles had chosen his moment unerringly, and his arguments lost nothing by the flowing accompaniment of the extra pint. They were, however, quite strong in themselves. The gist of them was that thus far we had remarkably little to show for what Raffles would call “our second innings.” This even I could not deny. We had scored a few “long singles,” but our “best shots” had gone “straight to hand,” and we were “playing a deuced slow game.” Therefore we needed a new partner—and the metaphor failed Raffles. It had served its turn. I already agreed with him. In truth I was tired of my false position as hireling attendant, and had long fancied myself an object of suspicion to that other impostor the doctor. A fresh, untrammelled start was a fascinating idea to me, though two was company, and three in our case might be worse than none. But I did not see how we could hope, with our respective handicaps, to solve a problem which was already the despair of Scotland Yard.

“Suppose I have solved it,” observed Raffles, cracking a walnut in his palm.

“How could you?” I asked, without believing for an instant that he had.

“I have been taking the Morning Post for some time now.”

“Well?”

“You have got me a good many odd numbers of the less base society papers.”

“I can’t for the life of me see what you’re driving at.”

Raffles smiled indulgently as he cracked another nut.

“That’s because you’ve neither observation nor imagination, Bunny—and yet you try to write! Well, you wouldn’t think it, but I have a fairly complete list of the people who were at the various functions under cover of which these different little coups were brought off.”

I said very stolidly that I did not see how that could help him. It was the only answer to his good-humored but self-satisfied contempt; it happened also to be true.

“Think,” said Raffles, in a patient voice.

“When thieves break in and steal,” said I, “upstairs, I don’t see much point in discovering who was downstairs at the time.”

“Quite,” said Raffles—”when they do break in.”

“But that’s what they have done in all these cases. An upstairs door found screwed up, when things were at their height below; thief gone and jewels with him before alarm could be raised. Why, the trick’s so old that I never knew you condescend to play it.”

“Not so old as it looks,” said Raffles, choosing the cigars and handing me mine. “Cognac or Benedictine, Bunny?”

“Brandy,” I said, coarsely.

“Besides,” he went on, “the rooms were not screwed up; at Dorchester House, at any rate, the door was only locked, and the key missing, so that it might have been done on either side.”

“But that was where he left his rope-ladder behind him!” I exclaimed in triumph; but Raffles only shook his head.

“I don’t believe in that rope-ladder, Bunny, except as a blind.”

“Then what on earth do you believe?”

“That every one of these so-called burglaries has been done from the inside, by one of the guests; and what’s more I’m very much mistaken if I haven’t spotted the right sportsman.”

I began to believe that he really had, there was such a wicked gravity in the eyes that twinkled faintly into mine. I raised my glass in convivial congratulation, and still remember the somewhat anxious eye with which Raffles saw it emptied.

“I can only find one likely name,” he continued, “that figures in all these lists, and it is anything but a likely one at first sight. Lord Ernest Belville was at all those functions. Know anything about him, Bunny?”

“Not the Rational Drink fanatic6?”

“Yes.”

“That’s all I want to know.”

“Quite,” said Raffles; “and yet what could be more promising? A man whose views are so broad and moderate, and so widely held already (saving your presence, Bunny), does not bore the world with them without ulterior motives. So far so good. What are this chap’s motives? Does he want to advertise himself? No, he’s somebody already. But is he rich? On the contrary, he’s as poor as a rat for his position, and apparently without the least ambition to be anything else; certainly he won’t enrich himself by making a public fad of what all sensible people are agreed upon as it is. Then suddenly one gets one’s own old idea—the alternative profession! My cricket—his Rational Drink! But it is no use jumping to conclusions. I must know more than the newspapers can tell me. Our aristocratic friend is forty, and unmarried. What has he been doing all these years? How the devil was I to find out?”

“How did you?” I asked, declining to spoil my digestion with a conundrum, as it was his evident intention that I should.

“Interviewed him!” said Raffles, smiling slowly on my amazement.

“You—interviewed him?” I echoed. “When—and where?”

“Last Thursday night, when, if you remember, we kept early hours, because I felt done. What was the use of telling you what I had up my sleeve, Bunny? It might have ended in fizzle, as it still may. But Lord Ernest Belville was addressing the meeting at Exeter Hall7; I waited for him when the show was over, dogged him home to King John’s Mansions8, and interviewed him in his own rooms there before he turned in.”

My journalistic jealousy was piqued to the quick. Affecting a scepticism I did not feel (for no outrage was beyond the pale of his impudence), I inquired dryly which journal Raffles had pretended to represent. It is unnecessary to report his answer. I could not believe him without further explanation.

“I should have thought,” he said, “that even you would have spotted a practice I never omit upon certain occasions. I always pay a visit to the drawing-room, and fill my waistcoat pocket from the card-tray9. It is an immense help in any little temporary impersonation. On Thursday night I sent up the card of a powerful writer connected with a powerful paper; if Lord Ernest had known him in the flesh I should have been obliged to confess to a journalistic ruse; luckily he didn’t—and I had been sent by my editor to get the interview for next morning. What could be better—for the alternative profession?”

I inquired what the interview had brought forth.

“Everything,” said Raffles. “Lord Ernest has been a wanderer these twenty years. Texas, Fiji, Australia. I suspect him of wives and families in all three. But his manners are a liberal education. He gave me some beautiful whiskey, and forgot all about his fad. He is strong and subtle, but I talked him off his guard. He is going to the Kirkleathams’ to-night—I saw the card stuck up. I stuck some wax into his keyhole as he was switching off the lights.”

And, with an eye upon the waiters, Raffles showed me a skeleton key, newly twisted and filed; but my share of the extra pint (I am afraid no fair share) had made me dense. I looked from the key to Raffles with puckered forehead—for I happened to catch sight of it in the mirror behind him.

“The Dowager Lady Kirkleatham,” he whispered, “has diamonds as big as beans, and likes to have ’em all on—and goes to bed early—and happens to be in town!”

And now I saw.

“The villain means to get them from her!”

“And I mean to get them from the villain,” said Raffles; “or, rather, your share and mine.”

“Will he consent to a partnership?”

“We shall have him at our mercy. He daren’t refuse.”

Raffles’s plan was to gain access to Lord Ernest’s rooms before midnight; there we were to lie in wait for the aristocratic rascal, and if I left all details to Raffles, and simply stood by in case of a rumpus, I should be playing my part and earning my share. It was a part that I had played before, not always with a good grace, though there had never been any question about the share. But to-night I was nothing loath. I had had just champagne enough—how Raffles knew my measure!—and I was ready and eager for anything. Indeed, I did not wish to wait for the coffee, which was to be especially strong by order of Raffles. But on that he insisted, and it was between ten and eleven when at last we were in our cab.

“It would be fatal to be too early,” he said as we drove; “on the other hand, it would be dangerous to leave it too late. One must risk something. How I should love to drive down Piccadilly and see the lights! But unnecessary risks are another story.”

II

King John’s Mansions, as everybody knows, are the oldest, the ugliest, and the tallest block of flats in all London. But they are built upon a more generous scale than has since become the rule, and with a less studious regard for the economy of space. We were about to drive into the spacious courtyard when the gate-keeper checked us in order to let another hansom drive out. It contained a middle-aged man of the military type, like ourselves in evening dress. That much I saw as his hansom crossed our bows, because I could not help seeing it, but I should not have given the incident a second thought if it had not been for his extraordinary effect upon Raffles. In an instant he was out upon the curb, paying the cabby, and in another he was leading me across the street, away from the mansions.

“Where on earth are you going?” I naturally exclaimed.

“Into the park,” said he.”We are too early.”

His voice told me more than his words. It was strangely stern.

“Was that him—in the hansom?”

“It was.”

“Well, then, the coast’s clear,” said I, comfortably. I was for turning back then and there, but Raffles forced me on with a hand that hardened on my arm.

“It was a nearer thing than I care about,” said he. “This seat will do; no, the next one’s further from a lamp-post. We will give him a good half-hour, and I don’t want to talk.”

We had been seated some minutes when Big Ben sent a languid chime over our heads to the stars. It was half-past ten, and a sultry night10. Eleven had struck before Raffles awoke from his sullen reverie, and recalled me from mine with a slap on the back. In a couple of minutes we were in the lighted vestibule at the inner end of the courtyard of King John’s Mansions.

“Just left Lord Ernest at Lady Kirkleatham’s,” said Raffles. “Gave me his key and asked us to wait for him in his rooms. Will you send us up in the lift?”

In a small way, I never knew old Raffles do anything better. There was not an instant’s demur. Lord Ernest Belville’s rooms were at the top of the building, but we were in them as quickly as lift could carry and page-boy conduct us. And there was no need for the skeleton key after all; the boy opened the outer door with one of his own, and switched on the lights before leaving us.

“Now that’s interesting,” said Raffles, as soon as we were alone; “they can come in and clean when he is out. What if he keeps his swag at the bank? By Jove, that’s an idea for him! I don’t believe he’s getting rid of it; it’s all lying low somewhere, if I’m not mistaken, and he’s not a fool.”

While he spoke he was moving about the sitting-room, which was charmingly furnished in the antique style, and making as many remarks as though he were an auctioneer’s clerk with an inventory to prepare and a day to do it in, instead of a cracksman who might be surprised in his crib at any moment.

“Chippendale of sorts, eh, Bunny? Not genuine, of course; but where can you get genuine Chippendale now, and who knows it when they see it? There’s no merit in mere antiquity. Yet the way people pose on the subject! If a thing’s handsome and useful, and good cabinet-making, it’s good enough for me.”

“Hadn’t we better explore the whole place?” I suggested nervously. He had not even bolted the outer door. Nor would he when I called his attention to the omission.

“If Lord Ernest finds his rooms locked up he’ll raise Cain,” said Raffles; “we must let him come in and lock up for himself before we corner him. But he won’t come yet; if he did it might be awkward, for they’d tell him down below what I told them. A new staff comes on at midnight. I discovered that the other night.”

“Supposing he does come in before?”

“Well, he can’t have us turned out without first seeing who we are, and he won’t try it on when I’ve had one word with him. Unless my suspicions are unfounded, I mean.”

“Isn’t it about time to test them?”

“My good Bunny, what do you suppose I’ve been doing all this while? He keeps nothing in here. There isn’t a lock to the Chippendale that you couldn’t pick with a penknife, and not a loose board in the floor, for I was treading for one before the boy left us. Chimney’s no use in a place like this where they keep them swept for you. Yes, I’m quite ready to try his bedroom.”

There was but a bathroom besides; no kitchen, no servant’s room; neither are necessary in King John’s Mansions. I thought it as well to put my head inside the bathroom while Raffles went into the bedroom, for I was tormented by the horrible idea that the man might all this time be concealed somewhere in the flat11. But the bathroom blazed void in the electric light. I found Raffles hanging out of the starry square which was the bedroom window, for the room was still in darkness. I felt for the switch at the door.

“Put it out again!” said Raffles fiercely. He rose from the sill, drew blind and curtains carefully, then switched on the light himself. It fell upon a face creased more in pity than in anger, and Raffles only shook his head as I hung mine.

“It’s all right, old boy,” said he; “but corridors have windows too, and servants have eyes; and you and I are supposed to be in the other room, not in this. But cheer up, Bunny! This is the room; look at the extra bolt on the door; he’s had that put on, and there’s an iron ladder to his window in case of fire! Way of escape ready against the hour of need; he’s a better man than I thought him, Bunny, after all. But you may bet your bottom dollar that if there’s any boodle in the flat it’s in this room.”

Yet the room was very lightly furnished; and nothing was locked. We looked everywhere, but we looked in vain. The wardrobe was filled with hanging coats and trousers in a press, the drawers with the softest silk and finest linen. It was a camp bedstead that would not have unsettled an anchorite12; there was no place for treasure there. I looked up the chimney, but Raffles told me not to be a fool, and asked if I ever listened to what he said. There was no question about his temper now. I never knew him in a worse.

“Then he has got it in the bank,” he growled. “I’ll swear I’m not mistaken in my man!”

I had the tact not to differ with him there. But I could not help suggesting that now was our time to remedy any mistake we might have made. We were on the right side of midnight still.

“Then we stultify ourselves downstairs,” said Raffles. “No, I’ll be shot if I do! He may come in with the Kirkleatham diamonds! You do what you like, Bunny, but I don’t budge.”

“I certainly shan’t leave you,” I retorted, “to be knocked into the middle of next week by a better man than yourself.”

I had borrowed his own tone, and he did not like it. They never do. I thought for a moment that Raffles was going to strike me—for the first and last time in his life. He could if he liked. My blood was up. I was ready to send him to the devil. And I emphasized my offence by nodding and shrugging toward a pair of very large Indian clubs13 that stood in the fender, on either side of the chimney up which I had presumed to glance.

In an instant Raffles had seized the clubs, and was whirling them about his gray head in a mixture of childish pique and puerile bravado which I should have thought him altogether above.

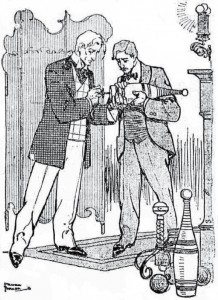

And suddenly as I watched him his face changed, softened, lit up, and he swung the clubs gently down upon the bed.

“They’re not heavy enough for their size,” said he rapidly; “and I’ll take my oath they’re not the same weight!”

He shook one club after the other, with both hands, close to his ear; then he examined their butt-ends under the electric light. I saw what he suspected now, and caught the contagion of his suppressed excitement. Neither of us spoke. But Raffles had taken out the portable tool-box that he called a knife, and always carried, and as he opened the gimlet14 he handed me the club he held. Instinctively I tucked the small end under my arm, and presented the other to Raffles.

“Hold him tight,” he whispered, smiling. “He’s not only a better man than I thought him, Bunny; he’s hit upon a better dodge than ever I did, of its kind. Only I should have weighted them evenly—to a hair.”

He had screwed the gimlet into the circular butt, close to the edge, and now we were wrenching in opposite directions. For a moment or more nothing happened. Then all at once something gave, and Raffles swore an oath as soft as any prayer. And for the minute after that his hand went round and round with the gimlet, as though he were grinding a piano-organ, while the end wormed slowly out on its delicate thread of fine hard wood.

The clubs were as hollow as drinking-horns, the pair of them, for we went from one to the other without pausing to undo the padded packets that poured out upon the bed. These were deliciously heavy to the hand, yet thickly swathed in cotton-wool, so that some stuck together, retaining the shape of the cavity, as though they had been run out of a mould. And when we did open them—but let Raffles speak.

He had deputed me to screw in the ends of the clubs, and to replace the latter in the fender where we had found them. When I had done the counterpane was glittering with diamonds where it was not shimmering with pearls.

“If this isn’t that tiara that Lady May was married in,” said Raffles, “and that disappeared out of the room she changed in, while it rained confetti on the steps, I’ll present it to her instead of the one she lost. . . . It was stupid to keep these old gold spoons, valuable as they are; they made the difference in the weight. . . . Here we have probably the Kenworthy diamonds. . . . I don’t know the history of these pearls. . . . This looks like one family of rings—left on the basin-stand, perhaps—alas, poor lady! And that’s the lot.”

Our eyes met across the bed.

“What’s it all worth?” I asked, hoarsely.

“Impossible to say. But more than all we ever took in all our lives. That I’ll swear to.”

“More than all—”

My tongue swelled with the thought.

“But it’ll take some turning into cash, old chap!”

“And—must it be a partnership?” I asked, finding a lugubrious voice at length.

“Partnership be damned!” cried Raffles, heartily. “Let’s get out quicker than we came in.”

We pocketed the things between us, cotton-wool and all, not because we wanted the latter, but to remove all immediate traces of our really meritorious deed.

“The sinner won’t dare to say a word when he does find out,” remarked Raffles of Lord Ernest; “but that’s no reason why he should find out before he must. Everything’s straight in here, I think; no, better leave the window open as it was, and the blind up. Now out with the light. One peep at the other room. That’s all right, too. Out with the passage light, Bunny, while I open—”

His words died away in a whisper. A key was fumbling at the lock outside.

“Out with it—out with it!” whispered Raffles in an agony; and as I obeyed he picked me off my feet and swung me bodily but silently into the bedroom, just as the outer door opened, and a masterful step strode in.

The next five were horrible minutes. We heard the apostle of Rational Drink unlock one of the deep drawers in his antique sideboard, and sounds followed suspiciously like the splash of spirits and the steady stream from a siphon. Never before or since did I experience such a thirst as assailed me at that moment, nor do I believe that many tropical explorers have known its equal. But I had Raffles with me, and his hand was as steady and as cool as the hand of a trained nurse. That I know because he turned up the collar of my overcoat for me, for some reason, and buttoned it at the throat. I afterwards found that he had done the same to his own, but I did not hear him doing it. The one thing I heard in the bedroom was a tiny metallic click, muffled and deadened in his overcoat pocket, and it not only removed my last tremor, but strung me to a higher pitch of excitement than ever. Yet I had then no conception of the game that Raffles was deciding to play, and that I was to play with him in another minute.

It cannot have been longer before Lord Ernest came into his bedroom. Heavens, but my heart had not forgotten how to thump! We were standing near the door, and I could swear he touched me; then his boots creaked, there was a rattle in the fender—and Raffles switched on the light.

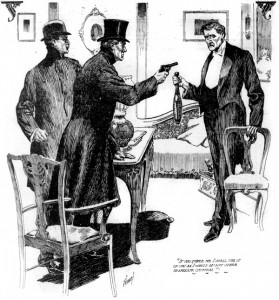

Lord Ernest Belville crouched in its glare with one Indian club held by the end, like a footman with a stolen bottle. A good-looking, well-built, iron-gray, iron-jawed man; but a fool and a weakling at that moment, if he had never been either before.

“Lord Ernest Belville,” said Raffles, “it’s no use. This is a loaded revolver, and if you force me I shall use it on you as I would on any other desperate criminal. I am here to arrest you for a series of robberies at the Duke of Dorchester’s, Sir John Kenworthy’s, and other noblemen’s and gentlemen’s houses during the present season. You’d better drop what you’ve got in your hand. It’s empty.”

Lord Ernest lifted the club an inch or two, and with it his eyebrows—and after it his stalwart frame as the club crashed back into the fender. And as he stood at his full height, a courteous but ironic smile under the cropped moustache, he looked what he was, criminal or not.

“Scotland Yard?” said he.

“That’s our affair, my lord.”

“I didn’t think they’d got it in them,” said Lord Ernest. “Now I recognize you. You’re my interviewer. No, I didn’t think any of you fellows had got all that in you. Come into the other room, and I’ll show you something else. Oh, keep me covered by all means. But look at this!”

On the antique sideboard, their size doubled by reflection in the polished mahogany, lay a coruscating cluster of precious stones, that fell in festoons about Lord Ernest’s fingers as he handed them to Raffles with scarcely a shrug.

“The Kirkleatham diamonds,” said he. “Better add ’em to the bag.”

Raffles did so without a smile; with his overcoat buttoned up to the chin, his tall hat pressed down to his eyes, and between the two his incisive features and his keen, stern glance, he looked the ideal detective of fiction and the stage. What I looked God knows, but I did my best to glower and show my teeth at his side. I had thrown myself into the game, and it was obviously a winning one.

“Wouldn’t take a share, I suppose?” Lord Ernest said casually.

Raffles did not condescend to reply. I rolled back my lips like a bull-pup.

“Then a drink, at least!”

My mouth watered, but Raffles shook his head impatiently.

“We must be going, my lord, and you will have to come with us.”

I wondered what in the world we should do with him when we had got him.

“Give me time to put some things together? Pair of pyjamas and tooth-brush, don’t you know?”

“I cannot give you many minutes, my lord, but I don’t want to cause a disturbance here, so I’ll tell them to call a cab if you like. But I shall be back in a minute, and you must be ready in five. Here, inspector, you’d better keep this while I am gone.”

And I was left alone with that dangerous criminal! Raffles nipped my arm as he handed me the revolver, but I got small comfort out of that.

“‘Sea-green Incorruptible?15‘” inquired Lord Ernest as we stood face to face.

“You don’t corrupt me,” I replied through naked teeth.

“Then come into my room. I’ll lead the way. Think you can hit me if I misbehave?”

I put the bed between us without a second’s delay. My prisoner flung a suit-case upon it, and tossed things into it with a dejected air; suddenly, as he was fitting them in, without raising his head (which I was watching), his right hand closed over the barrel with which I covered him.

“You’d better not shoot,” he said, a knee upon his side of the bed; “if you do it may be as bad for you as it will be for me!”

I tried to wrest the revolver from him.

“I will if you force me,” I hissed.

“You’d better not,” he repeated, smiling; and now I saw that if I did I should only shoot into the bed or my own legs. His hand was on the top of mine, bending it down, and the revolver with it. The strength of it was as the strength of ten16 of mine; and now both his knees were on the bed; and suddenly I saw his other hand, doubled into a fist, coming up slowly over the suit-case.

“Help!” I called feebly.

“Help, forsooth! I begin to believe you are from the Yard,” he said—and his upper-cut came with the “Yard.” It caught me under the chin.

It lifted me off my legs. I have a dim recollection of the crash that I made in falling.

III

Raffles was standing over me when I recovered consciousness. I lay stretched upon the bed across which that blackguard Belville had struck his knavish blow. The suit-case was on the floor, but its dastardly owner had disappeared.

“Is he gone?” was my first faint question.

“Thank God you’re not, anyway!” replied Raffles, with what struck me then as mere flippancy. I managed to raise myself upon one elbow.

“I meant Lord Ernest Belville,” said I, with dignity. “Are you quite sure that he’s cleared out?”

Raffles waved a hand towards the window, which stood wide open to the summer stars.

“Of course,” said he, “and by the route I intended him to take; he’s gone by the iron-ladder, as I hoped he would. What on earth should we have done with him? My poor, dear Bunny, I thought you’d take a bribe!17 But it’s really more convincing as it is, and just as well for Lord Ernest to be convinced for the time being.”

“Are you sure he is?” I questioned, as I found a rather shaky pair of legs.

“Of course!” cried Raffles again, in the tone to make one blush for the least misgiving on the point. “Not that it matters one bit,” he added, airily, “for we have him either way; and when he does tumble to it18, as he may any minute, he won’t dare to open his mouth.”

“Then the sooner we clear out the better,” said I, but I looked askance at the open window, for my head was spinning still.

“When you feel up to it,” returned Raffles, “we shall stroll out, and I shall do myself the honor of ringing for the lift. The force of habit is too strong in you, Bunny. I shall shut the window and leave everything exactly as we found it. Lord Ernest will probably tumble before he is badly missed; and then he may come back to put salt on us; but I should like to know what he can do even if he succeeds! Come, Bunny, pull yourself together, and you’ll be a different man when you’re in the open air.”

And for a while I felt one, such was my relief at getting out of those infernal mansions with unfettered wrists; this we managed easily enough; but once more Raffles’s performance of a small part was no less perfect than his more ambitious work upstairs, and something of the successful artist’s elation possessed him as we walked arm-in-arm across St. James’s Park. It was long since I had known him so pleased with himself, and only too long since he had had such reason.

“I don’t think I ever had a brighter idea in my life,” he said; “never thought of it till he was in the next room; never dreamt of its coming off so ideally even then, and didn’t much care, because we had him all ways up. I’m only sorry you let him knock you out. I was waiting outside the door all the time, and it made me sick to hear it. But I once broke my own head, Bunny, if you remember, and not in half such an excellent cause19!”

Raffles touched all his pockets in his turn20, the pockets that contained a small fortune apiece, and he smiled in my face as we crossed the lighted avenues of the Mall. Next moment he was hailing a hansom—for I suppose I was still pretty pale—and not a word would he let me speak until we had alighted as near as was prudent to the flat.

“What a brute I’ve been, Bunny!” he whispered then, “but you take half the swag, old boy, and right well you’ve earned it. No, we’ll go in by the wrong door and over the roof; it’s too late for old Theobald to be still at the play, and too early for him to be safely in his cups.”

So we climbed the many stairs with cat-like stealth, and like cats crept out upon the grimy leads. But to-night they were no blacker than their canopy of sky; not a chimney-stack stood out against the starless night; one had to feel one’s way in order to avoid tripping over the low parapets of the L-shaped wells that ran from roof to basement to light the inner rooms. One of these wells was spanned by a flimsy bridge with iron handrails21 that felt warm to the touch as Raffles led the way across! A hotter and a closer night I have never known.

“The flat will be like an oven,” I grumbled, at the head of our own staircase.

“Then we won’t go down,” said Raffles, promptly; “we’ll slack it22 up here for a bit instead. No, Bunny, you stay where you are! I’ll fetch you a drink and a deck-chair, and you shan’t come down till you feel more fit.”

And I let him have his way, I will not say as usual, for I had even less than my normal power of resistance that night. That villainous upper-cut! My head still sang and throbbed, as I seated myself on one of the aforesaid parapets, and buried it in my hot hands. Nor was the night one to dispel a headache; there was distinct thunder in the air. Thus I sat in a heap, and brooded over my misadventure, a pretty figure of a subordinate villain, until the step came for which I waited; and it never struck me that it came from the wrong direction.

“You have been quick,” said I, simply.

“Yes,” hissed a voice I recognized; “and you’ve got to be quicker still! Here, out with your wrists; no, one at a time; and if you utter a syllable you’re a dead man.”

It was Lord Ernest Belville; his close-cropped, iron-gray moustache gleamed through the darkness, drawn up over his set teeth. In his hand glittered a pair of handcuffs, and before I knew it one had snapped its jaws about my right wrist.

“Now come this way,” said Lord Ernest, showing me a revolver also, “and wait for your friend. And, recollect, a single syllable of warning will be your death!”

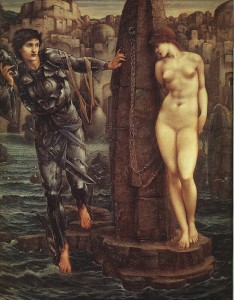

With that the ruffian led me to the very bridge I had just crossed at Raffles’s heels, and handcuffed me to the iron rail midway across the chasm. It no longer felt warm to my touch, but icy as the blood in all my veins.

So this high-born hypocrite had beaten us at our game and his, and Raffles had met his match at last! That was the most intolerable thought, that Raffles should be down in the flat on my account, and that I could not warn him of his impending fate; for how was it possible without making such an outcry as should bring the mansions about our ears? And there I shivered on that wretched plank, chained like Andromeda to the rock23, with a black infinity above and below; and before my eyes, now grown familiar with the peculiar darkness, stood Lord Ernest Belville, waiting for Raffles to emerge with full hands and unsuspecting heart! Taken so horribly unawares, even Raffles must fall an easy prey to a desperado in resource and courage scarcely second to himself, but one whom he had fatally underrated from the beginning. Not that I paused to think how the thing had happened; my one concern was for what was to happen next.

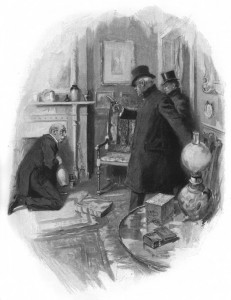

And what did happen was worse than my worst foreboding, for first a light came flickering into the sort of companion-hatch at the head of the stairs, and finally Raffles—in his shirt-sleeves! He was not only carrying a candle to put the finishing touch to him as a target; he had dispensed with coat and waistcoat downstairs, and was at once full-handed and unarmed.

“Where are you, old chap?” he cried, softly, himself blinded by the light he carried; and he advanced a couple of steps towards Belville. “This isn’t you, is it?”

And Raffles stopped, his candle held on high, a folding chair under the other arm.

“No, I am not your friend,” replied Lord Ernest, easily; “but kindly remain standing exactly where you are, and don’t lower that candle an inch, unless you want your brains blown into the street.”

Raffles said never a word, but for a moment did as he was bid; and the unshaken flame of the candle was testimony alike to the stillness of the night and to the finest set of nerves in Europe.

Then, to my horror, he coolly stooped, placing candle and chair on the leads, and his hands in his pockets, as though it were but a popgun that covered him.

“Why didn’t you shoot?” he asked insolently as he rose. “Frightened of the noise? I should be, too, with an old-pattern machine like that. All very well for service in the field—but on the house-tops at dead of night!”

“I shall shoot, however,” replied Lord Ernest, as quietly in his turn, and with less insolence, “and chance the noise, unless you instantly restore my property. I am glad you don’t dispute the last word,” he continued after a slight pause. “There is no keener honor than that which subsists, or ought to subsist, among thieves; and I need hardly say that I soon spotted you as one of the fraternity. Not in the beginning, mind you! For the moment I did think you were one of these smart detectives jumped to life from some sixpenny magazine; but to preserve the illusion you ought to provide yourself with a worthier lieutenant. It was he who gave your show away,” chuckled the wretch, dropping for a moment the affected style of speech which seemed intended to enhance our humiliation; “smart detectives don’t go about with little innocents to assist them. You needn’t be anxious about him, by the way; it wasn’t necessary to pitch him into the street; he is to be seen though not heard, if you look in the right direction. Nor must you put all the blame upon your friend; it was not he, but you, who made so sure that I had got out by the window. You see, I was in my bathroom all the time24—with the door open.”

“The bathroom, eh?” Raffles echoed with professional interest. “And you followed us on foot across the park?”

“Of course.”

“And then in a cab?”

“And afterwards on foot once more.”

“The simplest skeleton would let you in down below.”

I saw the lower half of Lord Ernest’s face grinning in the light of the candle set between them on the ground.

“You follow every move,” said he; “there can be no doubt you are one of the fraternity; and I shouldn’t wonder if we had formed our style upon the same model. Ever know A. J. Raffles?”

The abrupt question took my breath away; but Raffles himself did not lose an instant over his answer.

“Intimately,” said he.

“That accounts for you, then,” laughed Lord Ernest, “as it does for me, though I never had the honor of the master’s acquaintance. Nor is it for me to say which is the worthier disciple. Perhaps, however, now that your friend is handcuffed in mid-air, and you yourself are at my mercy, you will concede me some little temporary advantage?”

And his face split in another grin from the cropped moustache downward, as I saw no longer by candlelight but by a flash of lightning which tore the sky in two before Raffles could reply.

“You have the bulge at present,” admitted Raffles; “but you have still to lay hands upon your, or our, ill-gotten goods. To shoot me is not necessarily to do so; to bring either one of us to a violent end is only to court a yet more violent and infinitely more disgraceful one for yourself. Family considerations alone should rule that risk out of your game. Now, an hour or two ago, when the exact opposite—”

The remainder of Raffles’s speech was drowned from my ears by the belated crash of thunder which the lightning had foretold. So loud, however, was the crash when it came, that the storm was evidently approaching us at a high velocity; yet as the last echo rumbled away, I heard Raffles talking as though he had never stopped.

“You offered us a share,” he was saying; “unless you mean to murder us both in cold blood, it will be worth your while to repeat that offer. We should be dangerous enemies; you had far better make the best of us as friends.”

“Lead the way down to your flat,” said Lord Ernest, with a flourish of his service revolver, “and perhaps we may talk about it. It is for me to make the terms, I imagine, and in the first place I am not going to get wet to the skin up here.”

The rain was beginning in great drops, even as he spoke, and by a second flash of lightning I saw Raffles pointing to me.

“But what about my friend?” said he.

And then came the second peal. “Oh, he’s all right,” the great brute replied; “do him good! You don’t catch me letting myself in for two to one!”

“You will find it equally difficult,” rejoined Raffles, “to induce me to leave my friend to the mercy of a night like this. He has not recovered from the blow you struck him in your own rooms. I am not such a fool as to blame you for that, but you are a worse sportsman than I take you for if you think of leaving him where he is. If he stays, however, so do I.”

And, just as it ceased, Raffles’s voice seemed distinctly nearer to me; but in the darkness and the rain, which was now as heavy as hail, I could see nothing clearly. The rain had already extinguished the candle. I heard an oath from Belville, a laugh from Raffles, and for a second that was all. Raffles was coming to me, and the other could not even see to fire; that was all I knew in the pitchy interval of invisible rain before the next crash and the next flash.

And then!

This time they came together, and not till my dying hour shall I forget the sight that the lightning lit and the thunder applauded. Raffles was on one of the parapets of the gulf that my foot-bridge spanned, and in the sudden illumination he stepped across it as one might across a garden path. The width was scarcely greater, but the depth! In the sudden flare I saw to the concrete bottom of the well, and it looked no larger than the hollow of my hand. Raffles was laughing in my ear; he had the iron railing fast; it was between us, but his foothold was as secure as mine. Lord Ernest Belville, on the contrary, was the fifth of a second late for the light, and half a foot short in his spring. Something struck our plank bridge so hard as to set it quivering like a harp-string; there was half a gasp and half a sob in mid-air beneath our feet; and then a sound far below that I prefer not to describe. I am not sure that I could hit upon the perfect simile; it is more than enough for me that I can hear it still. And with that sickening sound came the loudest clap of thunder yet, and a great white glare that showed us our enemy’s body far below, with one white hand spread like a starfish, but the head of him mercifully twisted underneath.

“It was all his own fault, Bunny. Poor devil! May he and all of us be forgiven; but pull yourself together for your own sake. Well, you can’t fall; stay where you are a minute.”

I remember the uproar of the elements while Raffles was gone; no other sound mingled with it; not the opening of a single window, not the uplifting of a single voice. Then came Raffles with soap and water, and the gyve was wheedled from one wrist, as you withdraw a ring for which the finger has grown too large. Of the rest, I only remember shivering till morning in a pitch-dark flat, whose invalid occupier was for once the nurse, and I his patient.

And that is the true ending of the episode in which we two set ourselves to catch one of our own kidney, albeit in another place I have shirked the whole truth25. It is not a grateful task to show Raffles as completely at fault as he really was on that occasion; nor do I derive any subtle satisfaction from recounting my own twofold humiliation, or from having assisted never so indirectly in the death of a not uncongenial sinner. The truth, however, has after all a merit of its own, and the great kinsfolk of poor Lord Ernest have but little to lose by its divulgence. It would seem that they knew more of the real character of the apostle of Rational Drink than was known at Exeter Hall. The tragedy was indeed hushed up, as tragedies only are when they occur in such circles. But the rumor that did get abroad, as to the class of enterprise which the poor scamp was pursuing when he met his death, cannot be too soon exploded, since it breathed upon the fair fame of some of the most respectable flats in Kensington.